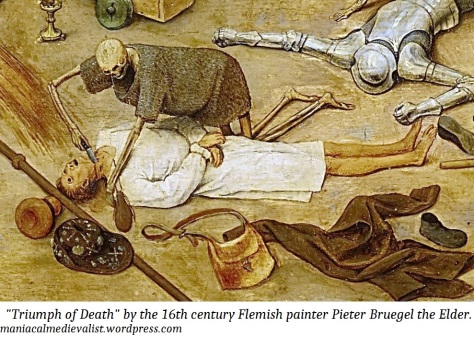

As I promised, here’s how I made my 16th century Flemish working-class woman’s white linen partlet. I found a cool painting that I forgot to include in my other Flemish partlet post.

No extant working-class woman’s partlets from 16th century Antwerp exists. The best I could find is a slightly out of period (1607) painting by Jan Breugel the Younger. The painting shows a “bleach field” – a large field where the washer women lay their laundry to dry. The best copy I could find is still blurry, but I am almost positive that the figure I’m pointing to is a partlet.

The pattern itself looked simple enough: one solid piece of fabric for the front and back and then a separate piece for the neck. However getting it to hang right was a trial. I did about 6 full cotton mock-ups and several more partial ones that were rejected immediately.

The pattern I settled on, of which I didn’t take any picture (by that time I was doubtful of ever finding one that laid right), was not the rectangle version I started with below.

Proto-type #1. Did not work.

Looking at it now, it would seem obvious that the shoulders would be way bulky on the area nearer the arms. No, no, no. This did not work. What I eventually ended up with looked more like this:

Once it was finished, it was obvious. The flaring out of the front pieces make the fabric on the shoulder ends much less, thus solving the bulging problem.

Totally unrelated: One of the things that has been a detriment to my teaching has been those “ah-ha, that should have been obvious” moments. When things finally click, I always feel like such an idiot. The solution should have been apparent the whole time is generally the way I think. I discount all those little gradual “ah-ha”‘that all added up to the big one. So then when I go to teach, I try to go straight to that “this makes perfect, logical sense” answer, and it doesn’t always work.

For example, I’m teaching my homeschool co-op class how to make and draw your own Celtic knots. The subject to any normal person should be fairly intimidating. I’ve been doing it for a few years now, and so it all seems logical. Last week, I tried to skip all of the baby steps and lead my class (of mostly 10 year olds) to that logical end. I got one student who caught on right away and a bunch of others who had no clue as to what I was getting to.

It’s not that I don’t remember the baby steps, I just think I’m an idiot for having to go through them and for not jumping to that end conclusion immediately. At times I give myself such little credit. I try to think of Columbus when I do that. There’s a story from after he came back from the Americas. He was at a dinner party, and the other guests were making fun of him. “So you think you made this big discovery! Any idiot could have just sailed west and eventually run across that land.”

Columbus picked up a cooked egg from his plate and challenged his fellow diners. “Show me how you can get an egg to stand on its smaller end.” The men tried getting it to balance for a few moments before they asked Columbus to show them. He took the egg and smashed it on to the table, small end first.

“Well that was obvious!” the guests shouted. Columbus then replied, “Yes, but you didn’t think of it.”

In other words, take pride in your “ah-ha” moments, even if it seems that the answer should have been obvious.

On to the parlet.

Once I had the pattern figured out, it was on to the cartridge pleats. Now, I love me some pleats, but cartridge pleats were sent from hell to torment us folk who have even a slight trace of OCD. Getting them to be perfectly even is not easy.

Carefully measure 1cm dots along 4 yards of 1 1/2″ fabric. It doesn’t have to be 4 continuous yards. I used the scraps that were left from cutting out the body. There were a total of 4 pieces – three that were about 1 1/4 yards and one that was about 1/2 yard. All of the fabric was ironed in half before I began marking.

Because I did not want an excessive amount of marks to wash out, I used long quilting pins to run a straight line with each mark.

Each mark equals 1 running stitch made at the top and 2 at the bottom (about 4 threads from the bottom edge and then another 4 threads up). I wanted my stitches as even as possible, so I used a magnifying glass to make sure each stitch was where it needed to be. The extra effort makes the pleats look nicer.

Each mark equals 1 running stitch made at the top and 2 at the bottom (about 4 threads from the bottom edge and then another 4 threads up). I wanted my stitches as even as possible, so I used a magnifying glass to make sure each stitch was where it needed to be. The extra effort makes the pleats look nicer.

Normally I would have used white thread for these spacing stitches. I used a dark color simply so that they would show up against the fabric.

At this point the pins are unnecessary, so pull them out. Yes, cartridge pleating is very tedious.

At this point the pins are unnecessary, so pull them out. Yes, cartridge pleating is very tedious.

By pulling all three threads, the pleats come together nice and evenly.

By pulling all three threads, the pleats come together nice and evenly.

Now do it again for all of the other lengths of fabric.

Now do it again for all of the other lengths of fabric.

Each length of fabric will probably take more than one piece of thread. Just leave a long enough tail on the end and tie them together once they are gathered.

Each length of fabric will probably take more than one piece of thread. Just leave a long enough tail on the end and tie them together once they are gathered.

The lengths of fabric can be sewn together post-gathering.

The lengths of fabric can be sewn together post-gathering.

I used and overcast stitch to bind the fabric edges.

I used and overcast stitch to bind the fabric edges.

Making sure that the pleated fabric is long enough.

Making sure that the pleated fabric is long enough.

Sewing one side of the collar onto the pleats.

Sewing one side of the collar onto the pleats.

One side of the collar is sewn on. At this point the pleating stitches are still in.

Make a double row of back stitches to make sure that the pleats stay.

Make a double row of back stitches to make sure that the pleats stay.

On the opposite side make a line of back stitches through the pleats to make sure that the pleats stay put.

On the opposite side make a line of back stitches through the pleats to make sure that the pleats stay put.

At this point, the gathering stitches are still in, but not necessary. Using a small, sharp pair of embroidery scissors, snip and pull the stitches out. I used scissor grip tweezers to pull the threads out without disturbing the pleats.

At this point, the gathering stitches are still in, but not necessary. Using a small, sharp pair of embroidery scissors, snip and pull the stitches out. I used scissor grip tweezers to pull the threads out without disturbing the pleats.

At this point I wish I had not used red as one of my contrasting thread color choices. Since the pleats so tight, when I pulled the red threads out, it left a trace of red color. It’s very faint, but it’s still there.

Stitch the other side of the collar on with 2 more sets of back stitches. Turn both sides of the collar down, and make a running stitch to tack the sides down to the pleats.

Stitch the other side of the collar on with 2 more sets of back stitches. Turn both sides of the collar down, and make a running stitch to tack the sides down to the pleats.

And that’s it!

Attach the collar to the partlet, hem the partlet and then it’s done.

Here are some great sites to for more ideas and extra help:

![]()