First, I finally got the fabric I’m going to use for the side-laced cotte dyed!!

Freshly Dyed Fabric

I love the color! I was thinking it would be a bit more blue-ish, but I am pleasantly surprised by the results. I put it next to my white muslin for comparison.

I ended up using Dharma’s fiber reactive procion colors:

One part #30A Emerald Green

One part #32A Electric Blue

And 3/4 part #46 Brilliant Blue

On to the Pleated Apron

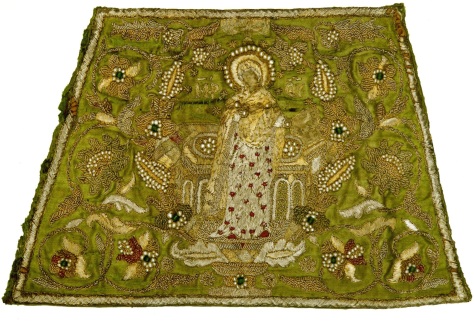

My first mock-up of the embroidered pleated apron is done! It’s a style of aprons that popped up around the mid 14th century and lasted until the late 16th century without changing much in style. I found a couple of new pictures demonstrating the over 200 year range of this accoutrement.

Luttrell Psalter

1320 – 1340 England

Detail from The Seamstress

Edward Schoen 1535

What I like, other than the bling quality, is that it makes the simple apron not so simple and allows it to be worn with fancier garb.

Last time I left off, I was having problems simply getting the dots straight. Here’s what I worked out.

That green thing in the upper right is a home-made Bat-a-rang I made for my son’s birthday party 3 years ago. I still find those things everywhere!

I made a perfect rectangle of a piece of cotton muslin by pulling threads. Here’s a quick and dirty tutorial on it: http://www.sewing.org/files/guidelines/4_204_straightening_fabric_grain.pdf

I squared the edges on my large fabric cutting board and used the marks to make a line nearly across the entire apron every half inch. Half an inch was too big on one of my previous attempts, but with the method I’m trying, it’s perfect.

Keeping the fabric still lined up on the mat, I marked every 1/2″ in the perpendicular direction. The fabric did slip quite a bit, so generally between each row I would re-straighten it on the mat. It doesn’t matter how many rows you make, but it needs to be an even number (we’ll get to that later).

At this point, I have eight long lines going across, and about 70 dashes going up and down.

Somewhere I read a tip that said do all of the gathering stitches at once. So I threaded 8 needles – I used sharp, medium length embroidery needles. I used normal DMC embroidery floss in a light, but not white color. Avoid the urge to use a completely contrasting color, like red. I did that with the cartridge pleats on my partlet, and when I pulled them out, it left red residue in the holes.

The method I used was I ran along the length-way lines. A smidgen before every dash, I pushed the needle through the fabric. Using the same motions used in a running stitch, right after each dash I came back up.

Tie the back ends of the thread together in batches of 2 and 3. It makes it easier to adjust when gathering the fabric.

When you get to the end of your threads, but still have more line to finish . . .

Start pulling the gathers. That’s why you tied the threads off at the other end and why it’s easier to work all 8 rows at once.

When I finished gathering the gathers, I thought that it looked way too small. I knew that I wanted the apron wider than this.

So I set about spreading the folds and trying my hardest to keep the columns straight. Then I laughed and realized that the smocking will loosen the gathers. I re-pulled the threads together, although not as tight as I did at first.

Take a chop-stick, or something like it, and pock into each pocket created by the gathered threads. It is tedious, but when you are done . . .

all of the rows line up nicely, and . . .

the front looks just lovely.

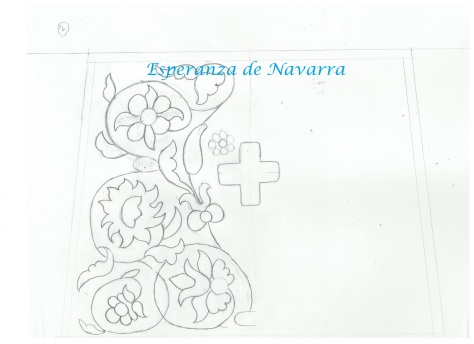

Now for the smocking. It helps if you understand the pattern first before the stitches.

The Pattern

- You are working with 2 rows at a time. That’s why you made an even number of rows.

- I labeled the columns to make it easier to understand.

- Remember: rows go side to side. Columns go up and down, like columns on a building. It’ll get confusing if I don’t make this distinction.

- Start at the lower LEFT of the whole damn thing. Believe me, it makes a difference. (Yeah, I tried starting on the right – a big mess)

- At the bottom left corner, Column A and Column B get stitched together. (Stitch explanations come in a minute).

- Then go up one row, and Column B and Column C get stitched together.

- Go back down one row and Column C and Column D get stitches together.

- Go up one row and Column D and Column E get stitched together.

- Go back down one row and Column E and Column F get stitched together

- And so on, and so on, until you finish those 2 rows.

- Here’s a little visual I threw together:

The Stitches

- Bring your thread up from the bottom on the leftish to middle part of the top of A. In this case, A is not at the end.

- Bring your needle around the other side of B and push it through both A and B.

- Do that one more time. Bring the needle around to the other side of B and go through B and A.

- Now bring the needle around again, but this time slip the needle into B only. You are going to run the needle up B to the row on top of it. BUT you are doing this under the cloth.

- Now you are going to do to B and C what you just did to A and B.

- And then come back down C to the first row.

- Now repeat with C and D. And then with D and E. And so on.

When you get to the end of the row:

- Connect the last two together and then tie your thread off underneath.

- Ignore the thread in the middle, it’s just a loose thread that got into the frame.

Starting a New Row

- Whatever you do, do NOT, I mean do NOT, just move on up to Row 3 and think you’re going to just work your way back to the left.

- It does NOT work that way. Yeah, I learned that the hard way too.

- Go back to the beginning of Row 3 all the way on the left.

- The pattern for Rows 3 & 4 is the same as for Rows 1 & 2

- Repeat again for Rows 5 & 6, and then 7 & 8.

- Keep doing it until you finish

Progression

All Done, At Least with the Smocking

- After the first two or three, I grew tired of having to tie off the loose threads in the back. The pleats are still fairly tight, and that made it a little more difficult.

- Once I was done with the smocking, I took out the gathering stitches.

- Loosened the pleats.

- Then I tied down all of the loose threads.

-

Front view

-

Back side

All that was left was to hem it and add the apron ties and waistband.

Do I like it? Yes, I think it is beautiful.

Can I improve on my techniques? Absolutely! Even looking back through the pictures I saw a couple of things I can do better on next time. All-in-all, smocking can be fun!

![]()